Transfer Restrictions for Closely Held Corporations

By Denice A. Gierach – May 13, 2010

Most people have investments that include stocks that are publically traded, with the New York Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. It is expected that shareholders will from time to time trade their shares. There are such large numbers of stock issued by a particular corporation that usually no transfer even affects who controls the corporation.

In a privately held company, usually the shareholders are the people who work the company and are corporate officers. Since the shares that can be issued are a smaller number, the principals in the privately held company generally wish to restrict who will end up being their “partner” in the business. They usual do not wish to have any outsider owing an interest in the business or even other family members, as it changes the dynamics of how the business is run.

To accomplish these restrictions, the shareholders enter into a buy-sell agreement which provides the obligations and sets in place certain restrictions on the disposition of the stock in a business when the shareholder leaves the business. These restrictions seek to avoid undesirable business associates and preserve existing business interests and are tempered by creating a market for the shares of the departing shareholder.

The buy-sell agreement (or an operating agreement in the case of a limited liability company or LLC) is a contract among the business owners and the company. Once the agreement is executed, it is binding on the company and the shareholders or members. Every new shareholder must agree to the terms contained in the agreement. This agreement sets forth who is able to make what decisions for the company, while certain decisions, such as the liquidation of the company, usually require a super majority or unanimous consent of the shareholders. Other decisions made in the normal course of business may be allocated to a particular shareholder or manager.

This agreement addresses when an owner retires or decides to withdraw from the business. One provision in the document requires that the departing shareholder first offer to sell his shares back to the remaining shareholders, and if the remaining shareholders do not wish to purchase the shares, then to offer the same option to the company. If none of the parties decide to buy back the shares, the departing shareholder is normally able to sell his shares outright to a third party.

If the departing shareholder receives an offer from an outside party for his shares, the departing shareholder must first offer his shares at the same price to the remaining shareholders, or if they do not wish to buy, then to the company.

If a shareholder has died or becomes disabled, similar provisions normally require the shareholder’s estate to sell the shares back to the other shareholders or the company. In that case, there may be a provision requiring the parties to get an appraisal to determine the value of the deceased shareholder’s interest or there may be a stipulated value that the parties have set each year.

Another circumstance for these types of provisions is when the shareholder has a spousal separation. Since the remaining shareholders do not want to deal with unwanted business associates, the shareholder undergoing the separation will have to sell his or her interest to the remaining shareholders or the company.

Sometimes the shareholders, although they worked well at the beginning of the company, have reached an impasse with the direction for the company in the future. Sometimes, the financial condition of the business requires additional capital from the shareholders and one of the shareholders is not able to further contribute or if the shareholder’s shares are subject to seizure from his creditors or there is an addiction problem by one of the shareholders. In those circumstances, these provisions protect the company to continue to operate freely after payment to the departing shareholder of a fair price for his or her shares.

These restrictions have been held to be valid by the courts. If there were no restrictive provisions, the shares in a closely held business would be readily transferable and would prevent the remaining shareholders from maintaining a desirable ownership structure. These restrictive covenants also create a market for the stock of a departing shareholder that did not exist before, and can allow for a smooth transition from the circumstances listed above.

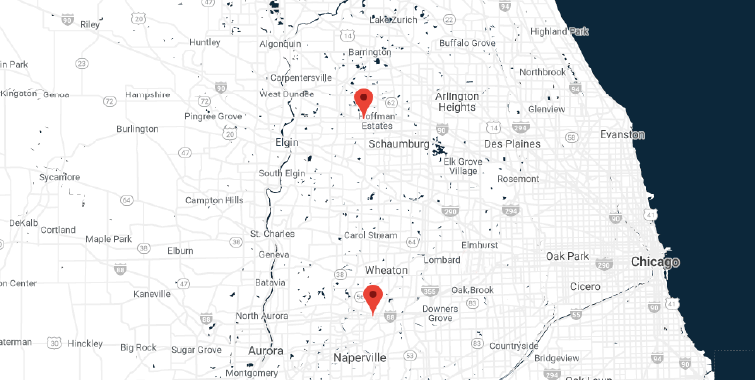

Denice Gierach is a lawyer and owner of the Gierach Law Firm in Naperville. She is a certified public accountant and has a master’s degree in management. She may be reached at 630-756-1160.

Practice Areas

Archive

+2018

+2016

Please note: These blogs have been created over a period of time and laws and information can change. For the most current information on a topic you are interested in please seek proper legal counsel.